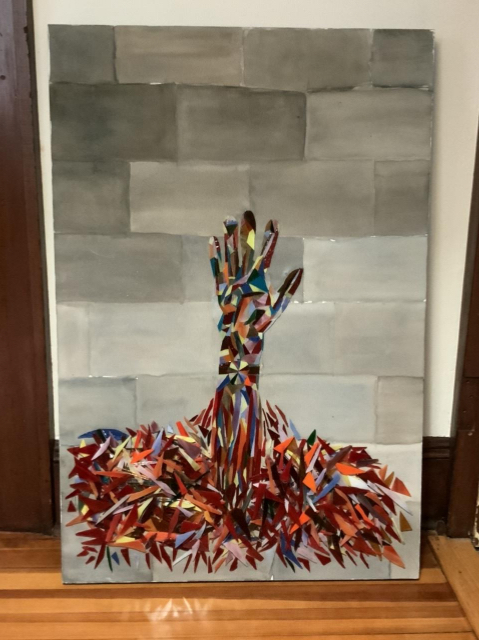

Kristallnacht

The name Kristallnacht, The Night of Broken Glass, comes from the shards of broken glass that littered streets following the organized violent pogroms across Germany and Austria on November 9-10, 1938. Under orders from Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels, Nazi Party paramilitary units of SS and Hitler Youth, accompanied by German civilians, rampaged through lewish neighborhoods, smashing windows, and destroying more than 1400 synagogues, and about 7500 Jewish homes, schools, and businesses along with killing 100- Jewish citizens. Thirty thousand Jewish men were arrested and sent to concentration camps such as Dachau and Buchenwald. This was the beginning of Hitler's "Final Solution" to eliminate the Jews of Europe and beyond.

Inspiration for the piece came from poetry and literature of a class Gail Ostrow taught at the Fairfield Senior Center on the Holocaust. This piece is meant to capture the foreboding, fear, and despair suffered by the victims of Kristallnacht.

Kristallnacht - Art glass shards on acrylic

Kristallnacht - Art glass shards on acrylic

Understanding Right Intention in Buddhism

I found the following excellent commentary that explains the principle aspects of Right Intention on Matthew Sockolov’s web site, OneMindDharm.com.

Right (or Wise) Intention

The Pali term we translate as right intention is samma sankappo, and is often translated as wise or right (samma) thought or intention (sankappo). As a part of the eightfold path, it is a foundational Buddhist teaching, and something about which the Buddha spoke repeatedly.

The Basics of Right Intention

We can take the Buddha’s words on wise intention and incorporate them into our daily lives. We can start with the traditional teaching of wise intention as the intentions of renunciation, good will, and harmlessness. These three intentions build the foundation of this teaching. We can investigate these intentions in our own experience, and see how they fuel our actions and speech.

When we’re a beginner to mindfulness, we may not see clearly how our intentions give rise to our actions. The Buddhist teaching on wise intention is intimately connected with wise action, as our intentions and thoughts often give rise to the ways in which we behave. Thus, as we purify our intentions, we can act from a place of kindness and wisdom.

Renunciation

The first intention offered traditionally is the intention of renunciation. This word may mean something different to a monastic than it does to a layperson, but the core of it remains the same. When you hear the word renunciation, you may think of the monk or nun who gives up worldly possession in pursuit of a spiritual life. Renunciation here is the intention, not necessarily the actual action.

In Buddhism, renunciation means we let go of attachment. Let’s say you are a layperson, living in a city. You likely have a roof over your head, food to eat, and water to drink. But you also may have a nice cell phone, a car, many clothes, etc. To practice renunciation doesn’t mean you need to get rid of these extras. Rather, you can cultivate non-attachment to these things. Attachment and clinging are one of the three unwholesome roots that lead to suffering.

In my experience, renunciation comes from a place of understanding what karma is. When we cling to things (material or spiritual), we are creating the conditions of suffering. We can cling to things like our cell phone, our favorite outfit, or the ease of mind from meditation. With right intention, we resolve to let go of these attachments, not to get rid of everything!

A perfect teaching on letting go and the inevitable uncertainty of experience comes from Ajahn Chah:

“Do you see this glass?” he said. “I love this glass. It holds the water admirably. When the sun shines on it, it reflects the light beautifully. When I tap it, it has a lovely ring. Yet for me, this glass is already broken. When the wind knocks it over or my elbow knocks it off the shelf and it falls to the ground and shatters, I say, ‘Of course.’ But when I understand that this glass is already broken, every minute with it is precious.”

Good Will

The second traditional wise intention is that of good will. This is taught as the opposite of ill-will, or wishing for others to be in pain. This can help us understand good will as the simple wish for others to be happy. If this sounds familiar to you, it may be because this is one understanding of metta, the Buddhist practice of loving-kindness. As one of the four brahma-viharas this is an important practice that helps us care for the wellbeing of ourselves and those around us.

In relation to right intention, we can check in with our intentions to see if we are wishing for others to be free and well, if we are wishing for others to experience suffering, or if we fall into indifference regarding the wellbeing of others or ourselves. We use mindfulness to recognize where our intentions are in a given moment, and to abandon the unwholesome intentions. We also can practice metta meditation in order to cultivate a mind and heart inclined toward caring and good will.

Harmlessness

The third and final intention is that of harmlessness. This includes harmlessness in actions, speech, and thought. We may understand this harmlessness as observing the training rules offered in the five precepts. A basic way to practice harmlessness, the five precepts offer us a way to take care of ourselves and our community.

With wise intention, we intend to cause no harm to ourselves or other sentient beings. We can watch when we intend to cause harm and when we are mindless about our intentions and their relation to causing harm. Sometimes we fall into craving or clinging and forget our intention to cause no harm. The cultivation of the intention of harmlessness comes through seeing clearly, practicing compassion, and being consistently aware of our intentions and actions.

Cultivating Wise Intention

Like any other teaching in Buddhist tradition, right intention is to be understood, worked with, and cultivated. It isn’t just a teaching about which we read and suddenly awaken. Rather, we put effort forth to cultivate this quality. As we practice more and more, wise intention comes more naturally.

Renunciation and Letting Go

To practice the intention of renunciation and letting go, we can do a few things. First, we can of course practice meditation! Below is a meditation on letting go you can use to cultivate this quality of renunciation.

We can also use mindfulness to notice the impermanence of experience, and how we cling and crave. Furthermore, we can tune into how our clinging and craving cause suffering. This understanding and wisdom can help us recognize in daily life when we fall into the intention of getting more, holding on, or avoiding. When we notice these intentions, we can make an effort to replace the thought with a thought of non-clinging or non-attachment.

Goodwill and Harmlessness

Metta practice really is one of the best ways we can cultivate the intention of good will. This is essentially the foundation of the teaching of metta. Here is a metta practice you can try. As we practice cultivating this quality more and more, we fall into the intention of caring for the wellness of others more easily.

Compassion practice can also help us to cultivate a wise and caring heart toward suffering, and lead us to the intention of harmlessness. When we tune in with wisdom to the experience of suffering, we see how painful it is. Below is a compassion practice you can use to cultivate a mind and heart inclined toward caring about suffering.

With harmlessness, it may be helpful to investigate the five precepts as a practice and investigation. Where do these precepts feel difficult for you? How can you use the precepts as the jumping-off point for an investigation into your intentions of harmlessness in the world?

Connecting Intention and Action

We can use the Buddha’s teachings to Rahula and reflect on our actions before, during, and after we act. Part of this is looking at the intention behind our actions. Were we acting out of love and wisdom, or out of fear and instinct? As we begin to cultivate wholesome intentions, we can see our actions follow suit.

One of the best examples of this is the teaching of generosity. In Buddhism, there are two separate qualities: dana and caga. Dana is generosity, and refers to the act of giving in a wholesome manner. Caga is the state of mind and heart which is inclined toward giving. When we cultivate a generous heart (caga), we practice generosity (dana) more often. This is a perfect illustration of how an intention can lead to an action, and how they are inter-related.

As we cultivate wisdom, loving-kindness, and compassion, the heart grows more inclined toward giving. As we grow in caga we take more generous action. It’s the same with many other things. When we cultivate anger or allow it to control us, we take more actions out of anger. When we cultivate the intention of ease and freedom, we take actions that lead us toward happiness.

One of the best ways we can use this as an investigation is by reflecting on actions we are taking or have taken. Ask yourself these questions:

- What was the intention behind our action?

- Does this intention lead to wholesome states and ease?

- Will this intention inflict harm or pain?

This is an opportunity to practice right intention and really bring your intentions to the forefront of your awareness. Sometimes we may find our intention was not clear to us in the given moment. If it doesn’t lead to wholesome states and ease, don’t encourage that intention by acting upon it!

One of Buddhism's main teaching for the path of the "Middle Way" is conducting yourself in accordance with the Five Precepts.

As revealed by the Buddha with the Four Noble Truths, it is possible to eliminate Dukkha(1) from our lives by taking the actions described in the Noble Eightfold Path.

"In order to get rid of suffering we need to eliminate the causes and conditions of suffering, and in order to achieve happiness we need to acquire the causes and conditions of happiness," notes the Dalai Lama.

By following the Eightfold Path (a.k.a. Middle Way), we can learn to think, act, speak, work, and manage our life and relationships with mindfulness, compassion, and empathy. As expressed by Ajahn Chan, “There is a middle way between the extremes of indulgence and self-denial, free from sorrow and suffering. This is the way to peace and liberation in this very life.”

The eight branches of the Path are grouped into the categories of Wisdom, Moral Conduct, and Mental Discipline.

Wisdom encompasses:

Right View / Understanding

Right Intention / Thought

Moral Conduct encompasses:

Right Speech

Right Action

Right Livelihood

Mental Discipline encompasses:

Right Effort

Right Mindfulness

Right Concentration

Note that the term “right” as used in Buddhist teachings is not taken as a synonym of good (as in good vs. evil) - in it has no moral significance. Instead, “right” is characteristic of action, words, or thoughts that generate happiness and inner peace for ourselves and others and drives us away from suffering.

The foundation of the Eightfold Path is recognizing and understanding the interdependence of cause and effect, called the doctrine of Karma/Vipaka. Karma is cause and is defined as any willful, intentional action we undertake having moral implications (actions that contravene any of the Five Precepts). Vipaka is defined as the effect of the karmic action; the resulting consequences of our actions. Karma and Vipaka mold and shape all that we have been and done, all that we have been told, all situations in which we have lived, and in every present moment as we consciously or unconsciously determine the future. Our life is both the Vipaka (effect) of the past actions and the Karma (cause) of our present and future actions.

The Buddha taught that Karma/Vipaka is not linear, because in any present moment we have the opportunity to chose our intention and action. The intricate interplay of the many threads of Karma/Vipaka, some reinforcing each other, some counterbalancing, some fading, some strengthening, is said to have been one of the realizations that came to the Buddha as he sat under the Bodhi tree.

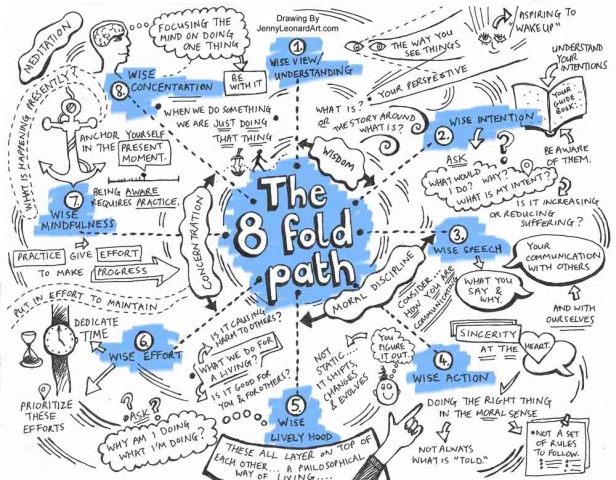

Each branch of the Noble Eightfold Path interacts with the other branches to support and encourage developing beneficial, mindful, and moral thinking, awareness, activity, and action. It also supports and encourages avoiding/abstaining from actions, activity, thinking, and awareness that have detrimental impact to oneself, to others, and to our natural environment. The following image depicts the complex interdependent nature of each of the branches.

Image courtesy of Jenny Leonard Art

1. Right View / Understanding - "Understanding" is sometimes translated as "knowledge" or "views." This principle involves the content and direction of our thinking; we are making an effort to stop mechanical, automatic thinking. We regularly question our old beliefs, attitudes, and assumptions. We endeavor to let go of egoism and egotism. Right understanding starts by acknowledging the suffering and difficulties in the world around us, as well as in our own lives. Then it asks us to deeply question and discover what we really care about, and to use that understanding as the basis of our spiritual practice. When we clearly see that things are not quite right in others and in ourselves, we also become aware of and explore other possibilities.

2. Right Intention / Thought - This is concerned with the character and quality of the emotional drives that underlie our thoughts. Through Right Understanding, we cultivate and develop thoughts and actions that are based on beneficial motivation. We move away from suffering from emotional blocks that interfere with clear thinking (e.g., greed, judging, jealousy, envy, fear, unfulfilled expectation, anger, lust, etc.). We become willing to work through and let go of old emotional and motivational reactions that may obstruct our clarity of thought and perception. "Wise Intention = motivation, inspired by understanding, to end suffering."

3. Right Speech - This frees us from: a commitment to always being "right," dogmatic or authoritarian statements, self-righteousness, and trying to make ourselves better by putting ourselves above others and causing them to feel less. Right speech avoids: lying of any type; gossip, malicious, vindictive, spiteful or slanderous talk; any talk intended to inflict pain, stir up hatred, or incite violence; telling secrets told in confidence; judgmental put-downs and other forms of oneupmanship; and other forms of speech that are not beneficial to oneself or others. It requires our ongoing intention and effort to be honest with oneself. Speaking less, we listen more.

4. Right Action - This element embodies the concepts of karma and vipaka described above. Right Action refers to keeping the five Precepts(2): i) not killing; ii) not stealing; iii) not misusing sex; iv) not lying; and v) not abusing intoxicants. The precepts are not commandments – they describe a mindful, harmonious, and compassionate way to live and respond to life's challenge.

5. Right Livelihood - This concerns the effort we expend acquiring the things need to sustain and live our life that do not compromise the Precepts of Right Action and which do not cause harm to ourselves, others, or the natural world. It is livelihood that is consistent with living ones life in accordance with the other seven branches of the eightfold path, and that can further our own spiritual development.

6. Right Effort - This involves cultivating skillful, peaceful habits of mind—especially insight, intuition, and willpower. Insight helps us perceive which of our usual and habitual states of mind are useful and valuable to preserve or strengthen, and which are unhelpful and deserving of our effort to discard.

7. Right Mindfulness - This focuses on developing our unconditioned awareness of the present moment based on: i) awareness of our body; ii) awareness of feelings; iii) awareness of mental phenomena (thoughts, emotions); iv) awareness of physical surroundings; and v) awareness of truths/laws of experience. In mindfulness, we are not asked to "think about" or conceptualize, but to simply "pay attention to." We develop equanimity (even-mindedness) and compassion, allowing us to see the world and our fellow humans clearly, without expectation, without judgment, without envy, without hatred.

8. Right Concentration - This is "cultivating a steady, focused, ease-filled mind." Right concentration refers to the cultivation of mental disciplines that further our ability to be mindful in the present moment. This can help us move away from "monkey mind" to the ability to maintain a clear and steady focus of our attention and awareness.

The challenges and the benefits of the eightfold path are in the fundamental grasp of each element and how to put each of the eight principles into practice. By misunderstanding them, we can go astray. This is where a capable and trusted teacher comes in.

Go to my “Links to Resources” page for links to Buddhist resources I’ve used as references.

(1) Dukkha

Often translated as suffering, dukkha is better understood as being unhappy or dissatisfied with something in our life and craving it were different. This could be feeling jealousy for what another may have, craving something that we do not have, or being in great physical or emotional pain and being unable to accept it as a condition of one’s life in the present moment.

(2) FivePrecepts

By respecting life, we work to protect all living things and this planet that sustains life.

By being generous, we give freely of our time and resources where needed. We do not exploit other people or resources for our personal gain. We act to promote social justice and well-being for everyone.

By refraining from sexual misconduct, we are mindful of the pain caused by sexual misconduct, we honor our commitments to others, and take appropriate action to protect others from sexual exploitation.

By not lying, we are always truthful and avoid language that instigates or causes enmity and discord, and we practice deep (mindful) listening to others.

By avoiding intoxicants, we nourish ours and others’ bodies with healthful food. We nourish our minds by avoiding types of ideas, information, materials, and people that are addictive, cause agitation, advocate hate and violence, promote or engage in forms of physical, emotional, or sexual misconduct or abuse, or advocate or engage in forms of social injustice. This includes books, newspapers, blogs, magazines, websites, games, or other forms of entertainments, as well as jobs and organizations that engage in intoxicating behaviors or manufacture, market, or sell things encouraging intoxicating activities.